.png)

Idaho's GemBlogs

a part of IDGenWeb Project

Idahoan Legacy Roots Series:

The Werry Family

Contributed by May 2, 2012.

The Cornish people were a hardworking and resilient people but never seemed to get ahead and lived with one foot always in poverty. For that reason in 1863, eighteen-year-old Thomas Werry crossed the ocean from England to America looking for new opportunities for himself and his siblings. Finding United States locked into turmoil of a Civil War, and unable to find work, he returned to England. Over the next eight years, Thomas and his Werry siblings spent many hours conversing about getting out of the mines of Cornwall, and trying their luck again in working across the ocean in the United States. There was land for them to claim. It was a country with much to offer. They did not want their children and grandchildren to live out their lives as Cornish miners.

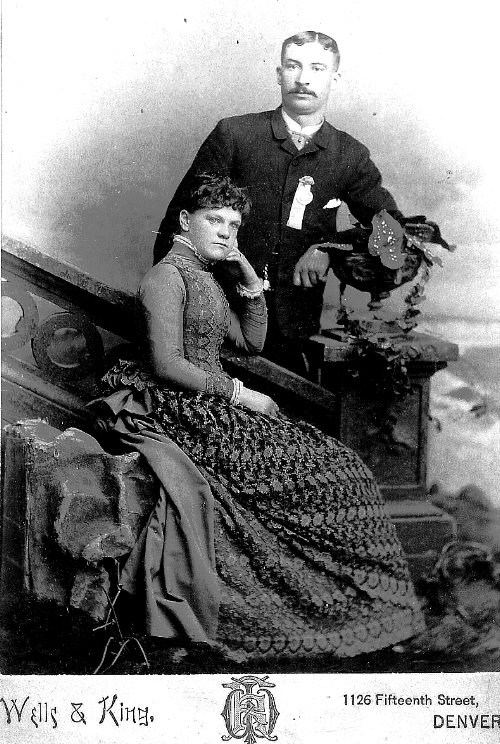

Joseph and Elizabeth Ann (Cobbledick) Werry

Finally in 1871, Thomas' brother Joseph Werry, and his wife, Elizabeth Ann Cobbledick sailed to America from Cornwall, England bringing three children with them. The family traveled from Liverpool on the ship "City of Antwerp" arriving in New York City on May 2 covering a distance of 3,300 miles in about three weeks. The ship's passenger list shows their names and ages: Joseph Werry, 28; Elizabeth, 26; Harry, 6; Joseph, 2 and Nicholas, an infant.

WERRY FAMILY IN ENGLAND

photos.htmlJoseph and Elizabeth Ann (Cobbledick) Werry & Sons

.jpg) The steamship, "City of Antwerp," was built in Scotland in 1866 for the sole purpose of making transatlantic voyages. It was 332 feet long by 39 feet wide. After hitting an iceberg in 1890, the ship sank, taking 43 lives. Like most immigrants of little means, the Werry family traveled either in "steerage" or "tween-deck." Normally, this area was used for cargo, so the passengers were actually in the cargo hold. The cargo ceiling height was usually around 6 to 8 feet high, and bunks of rough boards were set up along the wall sides. Each open bunk could hold several people and had straw or seaweed-filled mattresses where lice and fleas thrived. The immigrants were expected to bring their own pillows, blankets or animal hides for comfort. Wooden ladders were used to climb up to the hatch on the main deck from the narrow passageway below. The only ventilation came from that same hatch which allowed people in and out of the cargo-hold. In rough weather, it was closed causing the air to get very fetid, and turning the holding area dark as night. The food was poor, but edible and each person had to keep and wash their own dishes after each meal. Bringing extra food was advisable. The Werry family probably paid about 5 pounds (English currency) for each of their tickets . . . a small fortune. In England their last name was spelled Wherry. But in America, the "h" was dropped simplifying their name to "Werry."

The steamship, "City of Antwerp," was built in Scotland in 1866 for the sole purpose of making transatlantic voyages. It was 332 feet long by 39 feet wide. After hitting an iceberg in 1890, the ship sank, taking 43 lives. Like most immigrants of little means, the Werry family traveled either in "steerage" or "tween-deck." Normally, this area was used for cargo, so the passengers were actually in the cargo hold. The cargo ceiling height was usually around 6 to 8 feet high, and bunks of rough boards were set up along the wall sides. Each open bunk could hold several people and had straw or seaweed-filled mattresses where lice and fleas thrived. The immigrants were expected to bring their own pillows, blankets or animal hides for comfort. Wooden ladders were used to climb up to the hatch on the main deck from the narrow passageway below. The only ventilation came from that same hatch which allowed people in and out of the cargo-hold. In rough weather, it was closed causing the air to get very fetid, and turning the holding area dark as night. The food was poor, but edible and each person had to keep and wash their own dishes after each meal. Bringing extra food was advisable. The Werry family probably paid about 5 pounds (English currency) for each of their tickets . . . a small fortune. In England their last name was spelled Wherry. But in America, the "h" was dropped simplifying their name to "Werry."

photos.htmlPhotograph of the Left: Elizabeth Ann (Cobbledick) Werry.jpg)

Upon arrival in the United States, Joseph Werry's family began their move west. Joseph had never worked in coal mines because coal was not native to Cornwall. But, he had worked in the mines in Maryland and Ohio before taking his family on the train to Neva-da and the western boomtown mining camps. In Nevada, they worked in the silver and lead mines, then moved on to Colorado's gold and silver mines, and finally to Idaho's silver mines. Five of the eight Werry siblings eventually immigrated with their families to the United States. Each family worked in the mines in many states before meeting up together in Idaho to mine, farm or raise sheep. While Joseph and Elizabeth Werry and family traveled westward, several children were born to them. A son born in Maryland, he died shortly after birth. A daughter was born in Ohio, follow by three more children who were born in Nevada, though two had died in infancy. An-other son was born in Colorado, and the last child, a son, was born in Idaho where the family finally settled. Eleven known children were born to Joseph and Elizabeth Werry, one died in infancy in England. It took the family seventeen years to make their way from the immigrant ship to their final destination in Idaho.

photos.htmlPhotograph to the Right: Werry Brothers: Harry C. and Joseph

After their arrival in Nevada in 1875, the family lived in tents at a rough mining camp. The dry desert area had no water and no trees. In order to have water for cooking and drinking, it was packed in from the mine where it seeped from deep within the earth as pure, natural goodness. Joseph Werry had made yokes to fit the backs and necks of his sons, Harry (11), Joseph (6) and Nick (5). They would carry a five gallon bucket of water on each end of the yoke. Elizabeth being a pioneering woman, she was rugged and strong. The family eventually had rented a home so Elizabeth could keep a lodging house. She cooked for twenty men besides taking care of her own large family. Eight years later in 1883, the family left Nevada for Colorado, where the men worked in the Champion Mine at 10,000 feet elevation. Three years later, the family was persuaded to move to Bellevue, Idaho to work in the Minnie Moore Mine where they made $4 a day, good wages for those days. The Werry decided they liked Idaho and settled there per-manently. Their oldest son, Harry, had gone to Idaho before the other family member, but came back to the Colorado mines after they came to Idaho. He had a sweetheart in Colorado, and did not want to leave her.

.jpg)

WERRY FAMILY (1917)

photos.htmlJoseph and Elizabeth Ann (Cobbledick) Werry & Children

Harry Cobbledick and Lillian Mae (Carr) Werry

.jpg) On September 21, 1887 in Boulder, Colorado the oldest son, twenty-three-year-old, Harry Cobbledick Werry married, twenty-year-old, Lillian Mae Carr. Only five weeks after their wedding bliss, Harry had been working in the mines when a terrible accident occurred. The local Colorado newspaper, The Weekly Register Call reported the following story:

On September 21, 1887 in Boulder, Colorado the oldest son, twenty-three-year-old, Harry Cobbledick Werry married, twenty-year-old, Lillian Mae Carr. Only five weeks after their wedding bliss, Harry had been working in the mines when a terrible accident occurred. The local Colorado newspaper, The Weekly Register Call reported the following story:

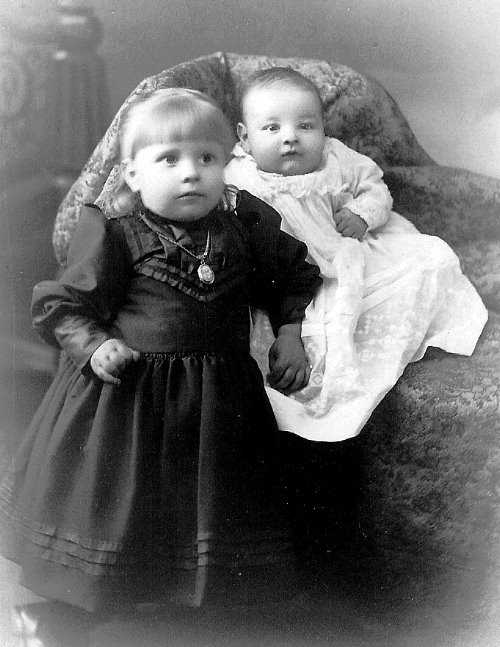

photos.htmlPhotograph to the Left: Harry C. and Lillian (Carr) Werry & children, Ezra J. and Mabel C.

ACCIDENT IN THE CLAYTON MINE

Harry Werry and his first cousin who are working in the Clayton mine on Gunnell hill, south of the Masonic cemetery, met with an accident this morning in drilling out a miss-shot hole. Harry, it appears, in working out the tamping, struck the cap attached to the stick of giant, and the explosive exploded. His right hand was badly lacerated and both eyes badly damaged. Drs. Davidson and Richmond are in attendance on Harry. His fellow workman is not badly injured.

LATER---since writing the above the Register-Call learns from Drs. Davidson and Richmond that they amputated the third and fourth fingers of the right hand of Harry Werry down to the wrist. The force of the explosion of the miss shot hole was such as to throw sand and rock into his face, lacerating his eyes. Doubts are entertained of his ever recovering his eyesight. This accident is a very sad one, the victim having been married about four weeks ago to a daughter of Mr. Ezra T. Carr, a former Gilpin county commissioner and resident of Russell, now a resident of Boulder County. Werry is receiving the best of attention at his residence on Nevada Street.

On November 4, 1887 one last notice appeared in the paper:

Harry Werry, the miner who was injured in the Clayton mine on Wednesday of this week, is being cared for by the members of Russell Lodge No. 40 I.O.O.F., of which he is a member.

I.O.O.F. stands for the Independent Order of Odd Fellows. "While Odd Fellows is not a religious institution, many of its principles and objectives are based upon the teachings of the Holy Bible and many of the rites and ceremonies, secret passwords, signs, and counter-signs have a Biblical origin or significance. One of its primary aims is to provide its members with aid when suffering because of illness, unemployment, or other misfortunes. The relief of members, of their families and close relatives, of their widows and orphans in case of death, appears to have been the chief purpose of the organization of Odd Fellowship in its beginning. These aims and purposes have been consistently and faithfully maintained throughout the history of the Order." (2010 Internet Search)

Left: photos.htmlHarry C. & Lillian M. (Carr) Werry's Wedding Photograph (ca. 1887)

Right: photos.htmlWerry Children, Mabel & Ezra Joe

In 1936 twenty-year-old Marge Werry, while studying at the University of Utah, wrote an English paper about her grandfather Harry Cobbledick Werry's accident. She entitled it:

UNDERGROUND TRAGEDY

It was early fall in the year 1887. Central City, Colorado, was a little mining town, just beginning to prosper from the vast amount of gold which its mines were producing. Some of the mines were so rich that when a rock containing the ore was broken apart, it would hang together by threads of gold, which was called "wire gold." Miners and their families were prospering, since gold was abundant and it sold for a fair price. Men came from long distances, staked claims, built homes among the foothills and in the valleys, and settled their families in this remarkable section of the country. Thus the fame of Central City continued to travel, bringing men and women, young and old alike, to its vast mountainous section, rich gold mines, gambling halls, smelly saloons, crowded dance halls and its variety of humanity. It was indeed a thriving little town which would someday develop into a city.

Harry and Lillian had met, had loved, and had married in the town, and a happier couple could not be found. Their love was beautiful, the kind that develops and becomes more firm and abiding as the years pass. They were devoted to each other; nothing could part them, ever. The couple moved into their new home which was built among the foothills, a short distance from the town. It looked just like any other little house in Central City, but there was something, an indefinable something, that made it dear to the two who owned it.

Harry and his Uncle Jack owned a mine called the "Emperor," which was only a mile from the young couple's new home. Harry would leave early in the morning and walk to work, carrying the lunch which Lillian had prepared for him. He would work far underground all day, digging shafts and tunnels farther into the earth and working on rich veins of gold in the walls of a drift. Often in the evenings before he went home, he would drill innumerable holes, insert the dynamite, light the long fuse, and hurry home in the dusk. A miner always waited until he was ready to go home in the evenings before he inserted the dynamite in the drills and lit the fuse. In the morning the fatal fumes from the exploded dynamite would have disappeared, and the miner could resume his work in safety. Harry would go home in the evenings, tired but happy, for didn't he have the sweetest wife in the world waiting for his return? Oh, it was good to be alive! It seemed impossible that anyone could be as happy as he was.

Days came and went, and the couple was blissfully happy for five short weeks, when the inevitable happened. The morning had begun in the usual manner. Breakfast was over and Harry had brought in an extra supply of wood and coal for his wife. Lillian put up her husband's lunch, kissed him goodbye, and watched him until he turned to wave to her before disappearing from view. Had they thought of it, they would have laughed at the idea of impending disaster. Nothing could impair such a passionate devotion they felt for each other. It would have seemed incredible to them had they known Harry would never see his wife again. It was too unreal. Fate couldn't be so cruel to them. Harry was joined by his Uncle Jack at the latter's house, and shouldering their pickaxes, the rest of their tools were at the mine, they walked along the path leading to the mountain. The younger man was extremely happy. Life was good to him; he had everything a man could wish for. There was nothing he lacked. Wouldn't Uncle Jack come over and help them make candy tonight? Yes, Uncle Jack would be glad for an excuse to get away from his lonely house. His wife had been dead a good many years, and he enjoyed the frequent visits with his niece and nephew.

They laughed and joked and were in high spirits when the mine was reached, then they went seriously to work. Harry descended into the excavation to resume the digging of a drift in which he had drilled dynamite the night before. A considerable amount of the bedrock had been blown into small particles, and every drill had exploded except one. It was a common occurrence for a drill not to explode, although when the miner "spooned" the dirt out and inserted dynamite again, he had to be very careful. It was so easy for the explosive to go off by the slight pressure or friction of removing the dirt which covered it. Harry decided he would drill again before he went home that evening, so he proceeded to another task. The day passed in much the same manner as a day passes in the life of a miner. In a short while, it was time to drill and go home. Harry was kneeling on the floor of the shaft scraping the dirt from the drill which had not exploded.

No one will ever know how it happened; it was all over in such a short time. When the dynamite exploded, the force was so great, it threw Harry down, but he was not knocked unconscious. Stunned and bleeding, he crawled on his hands and knees back along the shaft. But the darkness! And the excruciating pain! It must have been terrible. He will never know how he could tell where he was going, nor how he could crawl, maimed as he was. And the dangerous, stifling fumes from the explosion added to the torture. His lungs felt as if they must burst, and he lost so much blood that he would never have lived if Uncle Jack and two other miners had not heard the report of the explosion and found him in the shaft. They carried him home, three of them, for he was a large man. He was unrecognizable with his face blown half away, the empty, staring sockets where his eyes should have been, and one-half of his hand and arm dangling by a fragment of skin. Such a broken, bloody piece of humanity to take back to a woman married but five weeks! No one will ever know the torture, the agony, the intense suffering, both physically and mentally, the two people felt during the long months Harry lay in bed, close to death. He wanted to die, prayed that he would, but his wife's prayers were answered. She couldn't lose him; he meant so much to her. In his pain, discouragement and sorrow, her love had seemed to grow, not with pity, but a tender, protective affection as a mother for her child. She did everything she could to make his days of agony and suffering less painful. Her hours with him were a torture to her; a mental and physical anguish, yet she bore her pain in silence.

At last, after a year, he had improved enough to get up and feel his way ever so slowly around his once perfect home. After another six months, he was taken to Chicago to one of the best eye specialists in America. Nothing could be done. Harry's eyes had been blown completely away; only emptiness remained. His features were those of a stranger. Inside his cheeks and around his jaw and cheekbones, were particles of rocks which had become imbedded and the skin had grown over them. He carried horrible scars on his face all his life. Three maimed fingers remained on his right hand, the other half of his hand and arm were gone. Yet he could thank God he had been spared. Yes, he thanked God he was almost whole. More than anything, he thanked Him for his wife. She had remained faithful to him during every hour of his need. She loved him devotedly, a love which grew more beautiful through the years.

Two healthy children, a girl and a boy, were born to the couple, who dearly loved their son and daughter. Soon after, the family moved to Idaho, where they made their home. A few years later, the couple was blessed with a second son, who lived only twelve years. Harry was brave. He endured his affliction in silence, never aggrieving others and above all always cheerful. He was hurt intensely whenever he thought of his wife having to support the family, and he did everything he could to help make the journey through life easier for her. The things he could do were marvelous, and yet one would sigh in thankfulness for one's physical perfection. Harry lived for forty-four years, inspiring others with his cheerfulness and courage. (Margie Dawn Werry, 1936)

Ezra Joseph Werry

Margie's father, Ezra Joseph Werry, born in 1894 and named after his two grandfa-thers, Ezra Carr and Joseph Werry. Joe, as he has been called, was one of four children of Harry Cobbledick Werry and Lillian Mae Carr. A sister was stillborn in 1889, Mabel Clair born in 1890, and a brother Max born 1908, who died at 12 years of age in 1920 from complications of a flu. The accident that took Harry's eyes sights happened five years before Joe was born, thus he grew up only knowing a blind, crippled father. In 1903 when Joe was 11 years old, Harry and Lillian left Colorado and moved to Idaho to be near the rest of the Werry family. Joe from then on grew up in the Wood River area of Bellevue, Hailey, Ketchum, Carey and Sun Valley, Idaho.

Margie's father, Ezra Joseph Werry, born in 1894 and named after his two grandfa-thers, Ezra Carr and Joseph Werry. Joe, as he has been called, was one of four children of Harry Cobbledick Werry and Lillian Mae Carr. A sister was stillborn in 1889, Mabel Clair born in 1890, and a brother Max born 1908, who died at 12 years of age in 1920 from complications of a flu. The accident that took Harry's eyes sights happened five years before Joe was born, thus he grew up only knowing a blind, crippled father. In 1903 when Joe was 11 years old, Harry and Lillian left Colorado and moved to Idaho to be near the rest of the Werry family. Joe from then on grew up in the Wood River area of Bellevue, Hailey, Ketchum, Carey and Sun Valley, Idaho.

Photograph to the Left: Ezra Joseph "Joe" Werry

Margie, fifteen when her grandfather Harry died, remembers that he always had to have his food arranged on his plate like a clock face, such as meat at 6 o'clock, potatoes at 3 o'clock, etc. "Grampa would hold me on his lap and sing English songs to me such as "Mr. Mouse would a wooing go' and many others." Once she went into a dark room and found her grandfather there. "Grampa," she said, "turn on a light." He would replied, "I don't need it, Darlin'! I'm blind."

Left: photos.htmlHarry's Clock; Right: photos.htmlHarry Chopping Wood

She told of having ropes stretched from the main house to the outhouse so he could hold on to them and easily find his way to the outdoor toilet shanty that featured one hole and a catalog or corn cobs for wiping. He "built the board walk from the house to the woodshed and the barn. He chopped and sawed wood for the kitchen and front room stoves and I always marveled that he never cut himself," wrote Margie. The numbers printed on the family clock's face were faded from Harry's constant fingering of it to tell the time. Harry, though blind, could take care of the cows, chop wood, deliver the clean laundry and perform many other chores while Lillian took in boarders and did laundry to support the family. "Harry must have been very bright. He was labeled a math whiz. He could carry figures and solve algebraic equation in his head. He helped everyone, including the teachers at Bellevue High School." (Harry Marrick in "The Werry Family, the Early Years")

Family Stories & Photographs Courtesy of MaryAnne Butler Ashton

Submitted by

PDF Copy of the Story

IDGenWeb Project's Idahoan Legacy Roots | All Rights Reserved © 2012, 2017

About GemBlogs

Idaho's GemBlogs is a part of the IDGenWeb Special Project. This project is to post family history, stories, or perhaps genealogy or historical related of those with Idaho roots. To learn more about the project or how to post your query ... CLICK HERE

Past GemBlogs

Select a topic below to expand the menu of those available links

.gif) This special project is a part of the IDGenWeb Project. All rights are reserved by the project and its contributors.

This special project is a part of the IDGenWeb Project. All rights are reserved by the project and its contributors.

The IDGenWeb Project 2012 - 2017

Last Updated: 11/12/2017

Idaho's GemBlogs © 2017 | All Rights Reserved

A Part of The IDGenWeb Project